India Travel writing

Akbar’s city of dreams

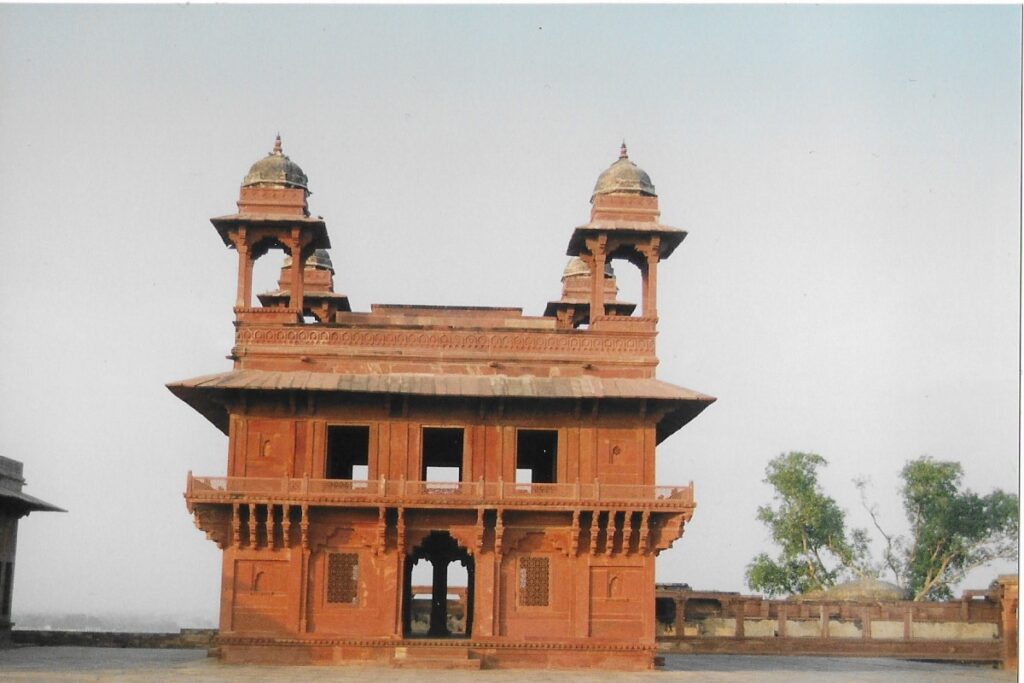

The ghost city of Fatehpur Sikri straddles the crest of a rocky ridge, thirty-seven kilometres from Agra, the town of the Taj. It was completed in 1585 by the great Moghul emperor Akbar. However, by 1600 its meagre water supply had proved incapable of sustaining the local population and and it has lain silent ever since.

Akbar was widely regarded by other Indian leaders of his day as an astute diplomat, as well as a gifted military strategist. Most notably though, the gains he made in territory were linked to a regime of religious tolerance, developed through discussions with representatives of the major faiths.

The events surrounding the founding of Fatehpur Sikri reads like a medieval fairy tale. Akbar came to Agra in search of the renowned Sufi mystic and holy man, Sheik Salim Chishti, to seek his blessing and to ask him to pray that Akbar’s wife might give birth to a son. Soon a son was born. In honour of the mystic, Akbar vowed to found a new city nearby.

On the face of it, this might just sound like a load of poppycock, a local legend, nothing more. It might be far easier to run with the simpler alternate version, which reckons that he just got fed up off with the crowds and noise of Agra and decided to relocate. Although if this version were true, there is a certain irony to it. The current frenetic experience that is Agra, is increased in no small part by the swarms of tourists who come to view the Taj and its satellite mausoleums – monuments which were erected some seventy years after Akbar. Add to this the havoc now wreaked by the internal combustion engine and, well, if he really had got fed up with the bedlam, he did not know he was born. What would he have made of it now?

Whichever version you chose to believe, what is not in doubt is that it was Akbar who commissioned the building of Fatehpur, and that in a variety of ways it is evidence of his ruling philosophy which sought to develop a synthesis of all religious beliefs – A society where all faiths were able to flourish.

The result, a palace complex which embraced his unorthodox philosophy, fusing both Hindu and Muslim architectural and artistic traditions.

The citadel is immaculately preserved. This masterpiece in sandstone glows in subtly changing shades of pink and red as the day progresses and the light fades. Its walls, mosque, palaces, baths, royal mint, courts and gardens now stand in splendid homage to an emperor who was perceived to be a great visionary – a kind of Mahatma Gandhi, only with wealth, bricks and a certain territorial ambition.

Inside the mosque’s courtyard, the very existence of the exquisite marble mausoleum of Akbar’s Sufi hero Sheik Salim Chishti is further evidence of the accommodation of architectural styles from different religions – Sufis did not embrace wholly or solely any one religion. They were in effect pluralistic mentors, for all their faithful followers across a range of creeds.

At the mausoleum’s lavish, staccato white marble canopy, pilgrims still come in droves to offer flowers, tie floral garlands to the latticed screens and, so it seems, to pray for the gift of a son.

Akbar’s city of dreams attracted many travellers during its short history as a lived in city. However, the Taj Mahal has long since put paid to that.

Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India

Fatehpur Sikri, Kiraoli, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, 283110, India

Bharatpur, Rajasthan, India

Stairways and salesmen

Beneath Akbar’s legacies are huddled a smattering of guest houses. If Fatehpur ever managed to restore its popularity stakes to times of former glories, these would multiply considerably, changing its laid-back atmosphere forever.

Within a few minutes of off-loading my bags at one of these establishments, I headed for the main mosque – the Jami Masjid – one of the biggest in India. I arrived at its Great Gate, a huge arched entrance, which scaled a height of two hundred feet. ‘Drama!’ this monolith screamed. The feeling was accentuated in no small part by the Gate sitting on top of a sheer set of imposing steps, which also rose by many feet.

The climb to the top was not for the faint hearted and not just because of any allergy to vertigo. For each steep stride up this staircase, from the market stalls at the bottom to the plateau at the top, I was encircled and plagued by a crowd of persistent touts from the ages of six to sixty. This was intense stuff. Agra is also notorious for its aggressive hawkers, which is not surprising given the influx of visitors attracted by the Taj, but at least it is spread widely across the town, rather than along a single set of steep grandiose steps.

Perhaps being the only visible Westerner turned me into a peddler’s magnet. Oh well, I thought, as I set foot on the first step, better to get it all over with in one dose.

And so the diatribe from this revolving circle of irritants that surrounded me commenced. Each tout had his own patter and brand of dubious merchandise to hawk:

‘I sell …..’

‘You buy …. ‘

‘I show you all the best views in the mosque …’

‘How many Rupees for your watch? ….’

‘You buy this marble elephant ….. ‘

‘You want backgammon, or maybe chess? ….. ‘

‘I get you very nice Indian lady, very nice bardy …’

‘You want good hotel?…..’

‘Here look – you buy my postcards OK?’

‘You want money change? …..’’

‘How about some opium?’

‘I show you my father’s shop. …’

‘You want guide? Me very good guide, only 300 Rupees.’

I trudged my way, bit by bit, to the gateway at the top. Miraculously, when I finally arrived, I had not parted with a single Rupee.

Thought for the Day

On reaching this summit, I stopped for a breather and stared up at the dome like ceiling of this huge gate. It was not a sandstone colour, in keeping with the rest of the structure. Rather large patches of black dominated. This was not caused by deterioration of the stonework, but by a series of giant sized bee hives.

I left the swarm of touts in my wake, passed underneath the more deadly swarm above my head and stopped purposefully to survey a certain quotation that Akbar had had carved on the other side of the entrance. It was a fitting inscription to have raised in a place like this and wouldn’t have been a bad epitaph for the chap. I have read several varying translations of it over the years. Quite loosely it goes something like this:

‘The world is a bridge, build no houses on it, the world endures for but an hour. Spend it in devotion, the rest is unseen.’

And its author? One Jesus Christ.

I was standing inside a Muslim place of worship, in an overwhelmingly Hindu country looking at a Christian quote.

A number of meanings could be attached to the quote, but right there and then it seemed to be saying, ‘Look folks, over the grand passage of time, all of us are only on this planet for a very tiny period indeed, so life is too short to fall out, especially over something as mumbo jumbo like religion. Why can’t we just treat all these strands of world thought as sort of right in their own way. After all none of us will really know for sure exactly which faith, if any, is correct until we make it to the other side.’

Well, that was my thought for the day, as I reflected on what felt like an ‘equal opportunities mission statement’ on religion from the start of the first millennium.

I switched my thoughts back to more earthly and fathomable matters.

Chess, backgammon and camels

The self-appointed salesmen on the mosques’ steps had receded to a trickle. They were no longer quite so ‘in my face’, more like a couple of strides behind. However, as I walked around the inner courtyard attempting to absorb the atmospheric surrounds these irritants continued to test my tolerance level.

Ever since my first visit to India, I have always been impressed by the astuteness of these touts. They come in many shapes and sizes, but particularly for those that have not even reached adolescence, it is apparent that for many youngsters in India becoming street wise pretty fast is an essential requirement of life.

In open competition, a Western kid of primary school age would not last ten minutes here. It would take him a lifetime to master all the tricks of the trade that a twelve – year-old tout in this continent has up his sleeve – an essential blend of skills that enables them to negotiate, anticipate, know a thing or two about telepathy and psychology, and possess a working knowledge of all major exchange rates.

Invariably, these essential attributes are channeled into that well acquired trick – persuading you to buy something that you really did not want in the first place. This occurs when after half an hour of persistent ‘in your face’ nagging, you start to think, well maybe the item in question might be of some use after all. It might just be worth trying to arrive at a mutually agreeable price, to get the little git off your back.

So, as I strolled across that courtyard, oh no, another chess set was thrust up into my face,

‘You buy chess set?’

‘No’

‘Why not?’

“Because I don’t like it.’

‘But you have not even looked at it.’

‘That’s right I have not looked at it and I have no intention of doing so,’ I said staring straight ahead.

‘But you should not just think about yourself – It is a nice present for girlfriend. Yes?’

‘It’s too early for me to start buying presents yet.’

‘Not too early – you cannot buy these chess sets outside of Fatehpur Sikri. They are only made locally. Once you leave here your chance is gone.’

‘But I do not like the design.’

‘Why not like the design?’

‘It’s round and square is more beautiful.’ (That should see him off, I thought.)

‘That’s ok, I can get a square one for you within ten minutes.’

Then I made the cardinal mistake of staring at the hand carved chess set for two complete seconds – Cue for him to move in for the kill.

‘Ok, here, take.’ he thrust the chess set into my hands.

‘No, too expensive.’

‘No too expensive, only two-hundred.’

‘Hah’, I sneered and handed it back, but this ten-year old’s hands were firmly out of sight, thrust behind his back.

‘Ok, sir you tell me how much. Whatever you offer is fine by me.’ And now he started to get really adventurous, and whipped a backgammon set out of his other pocket.

‘Sir how much for the two’.

I start to get a bit greedy ‘Two hundred’ I said, as much to test market conditions as anything else.

‘Ok, two hundred I take’, he said, dropping the chess and backgammon sets into my shoulder bag.

I start to hand over the Rupees, and he looks in horror ‘No Rupees Mister, only Dollaaahs, two hundred Dollaaahs you must pay me now please.’

‘Hah’ I said, removing the twin sets from my bag, placed them on the floor and walked away.

He picked the offending items up and caught back up with me ‘Please sir? Maybe just one set then? Yes’

‘Ok, I give you one hundred Rupees for the backgammon, no more, it’s only a small set.’

This ten-year-old then proceeded to give me a lecture on the fundamentals of the local economy and prevailing market conditions.

‘But Mister, one hundred Rupees is the cost price of the manufacturer, then he adds a price onto my price, then there has to be my propheeet.’ Gazing hopefully from four foot up to six foot four. He said ‘You understand me? Business is business. One hundred and fifty Rupees is not a laarrt, – One pound ninety I think, yes?’

‘Look, I really don’t want it anyway, but I will give you one hundred and twenty. ‘My last offer, OK?’

‘Here you are.’ I said handing over the money and squeezing the backgammon set into my trouser pocket, ’Now bugger off’.

Frequently at the end of cat and mouse bartering sessions like these, I think of a 1970s film (the title is still buried inside of me somewhere), that stared Peter Cook and Dudley Moore as two bungling misfits, trying to navigate their way through Morocco. At one point Cook is in the heart of a medina, waiting impatiently for Moore, who is late for their rendezvous. Eventually Moore shows up, with a camel in tow.

‘Where on earth did you buy that,’ asked Cook, with great incredulity.

‘Oh, I didn’t buy it,’ replied Moore”

‘Didn’t buy it? Didn’t buy it?’

‘No, I didn’t buy it. Someone sold it to me.’

Not that I could compare having a camel off-loaded onto me with purchasing a chess set. Getting it through customs might be problematic for a start.

A dark side of India

Amongst the handful of buildings that were highlighted on my spartan map was a government tourist complex and so later that evening I left the guesthouse and slipped off under cover of darkness, in search of some decent food and beer. Sorties after dark, away from large Indian towns and cities is a bit of a precarious venture and this felt no different – no lighting or footpaths of any kind, pitch black roads, and articulated trucks that come thundering around the bend and down the highway, with their headlights on full beam, dazzling you like a cat caught in the spotlight.

Half a mile later, relieved to have got there in one piece, I arrived at the slip road which led down to the tourist complex. At the bottom, beneath some dimly lit spotlights was a clutch of regulation issue Ambassador cars, for the professional and middle classes. I ventured down the path and entered the main reception.

Well, how inconsiderate of me, it was after all past 10 pm and the place was like the Marie Celeste. I rang the bell. Eventually a member of staff appeared and pointed me in the direction of the restaurant. I entered a lavish banqueting suite, with several long tables, kited out with silverware and china, but alas no diners, just a sleeping waiter, who woke up from his slumber and guided me to a seat.

Wary of the surrounding opulence, I picked up a menu, which not surprisingly had five-star prices. This wasn’t really the kind of place for your average tourist – ‘Tourist Complex’ was a bit of a misnomer in this case. It was more like an upmarket conference centre.

‘Something to eat Sir?’

‘Maybe I’ll just settle for a beer’ I said rather sheepishly. I walked back down the corridor to the bar, which was equally lifeless. I rang the bell, and the same sleeping waiter appeared from the restaurant. He was joined by the manager and his assistant, who were looking for a distraction to alleviate their boredom

The waiter poured a bottle of beer and asked ‘Sir, which room number shall I charge the beer to?’

‘No room number, I am not a resident.’

‘But where are you staying’ asked the manager.

‘The Godervan Guest House’

‘So, you came here by taxi’ he stated.

‘No, I walked.’

‘But sir, that is a fifteen-minute walk.’

‘Yes, I know, but I have legs, look here they are.’

‘Sir, you do not understand. This is rural India and in rural India no one walks alone after dark.’

‘But why?’ I asked.

Many times, I had heard this kind of advice during the preceding two weeks, … ‘Take care’, ‘Be very careful’, ‘Watch where you are going’, ‘Be careful who you talk to’, ‘Don’t walk alone’, ‘Don’t stay out too late’ – I could have compiled my own personal safety dictionary from these comments. People freely offered this advice but tended to be rather coy when asked to spell out the reasons behind their comments.

Here are a couple of examples:

Darkness according to Yogendra

Earlier that afternoon, I was standing on the top of the citadel wall that surrounded Fatehpur’s ancient buildings. I looked down on the plains below. The sun was starting to set. In the distance, there were many crumbled remains dotting the landscape, whose brickwork in the last rays of daylight was now a glowing amber. I wanted to take a closer look at this atmospheric ruin strewn environment, which felt like a spillover from this once opulent city. I descended from the top of the wall to ground level and followed the overgrown and bumpy path which wove its way through these dilapidated remains.

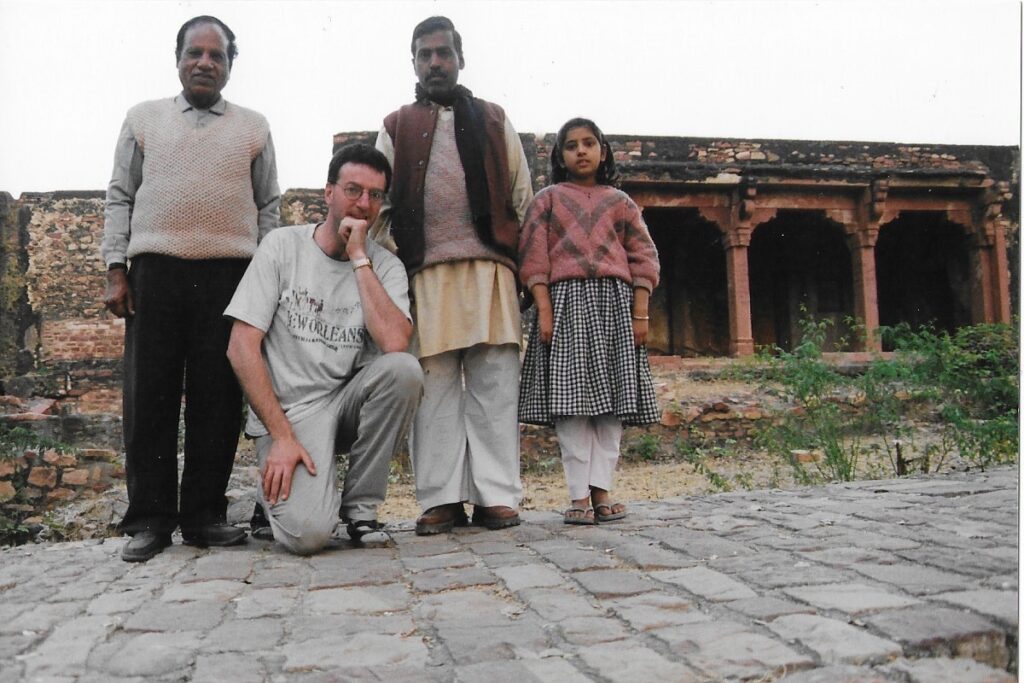

As the sun disappeared from the horizon and the sky turned crimson, I could see a posse of silhouettes coming down the track. Moments later Yogendra Dixit, his twelve-year-old daughter and uncle introduced themselves.

Yogendra wedged both thumbs in the pockets of his long flowing smock and letting both hands hang accordingly, puffed out his chest and fired a series of questions, as though in training to be a barrister.

Most of these contained the usual mix of banal queries:

‘Sir we would like to know to which country are you coming from.’

‘Sir, to which name are you called?’

‘Mister Damian, what make of camera you have here?’

‘Mister Damian, which profession have you?’

‘Mister Damian, how many years have you?’

However, this exchange of words then started to get more bizarre. He slipped effortlessly from asking about my date of birth to researching the height of Western architecture.

‘Mister Damian, tell me how long are the buildings in London? How many floors tall are they?’

‘Oh, many different sizes’ I replied.

‘Yes, but how many floors on average?’

Oh, twenty-two floors high on average’ I replied authoritatively.

Finally, as they were about to depart, Yogendra gives me the benefit of his wisdom. ‘Mister Damian, please you must go straight home now, along this path. Don’t stay here after dark.’

I had no intention of limbering, but none the less asked him to spell out his reasons. He played with a number of answers in his mind, looking for one which would not indicate that the town was riddled with dubious characters. Finally, he blubbered, ‘Because after dark many tigers roam these fields.’

And there was me thinking that the Brits hunted them to near extinction in the early part of the twentieth century. But, if tigers still roamed these parts, I am sure that they were just as happy to attack by daylight. Just in case, though, I went straight home.

A dark side of Agra

A few days before Yogendra had spun me the tale of ‘The Tigers of Fatehpur’, the hotel manager in Agra looked at me in alarm as I headed past reception at 9 pm, down the path and towards his locked gates.

‘Please Sir, where are you going?’ he called out with urgency.

‘To explore’

‘Very well, if you insist. My assistant will unlock the gates for you. But please, you must not walk too far and don’t stay out too long.’

‘But why?’ I demanded to know.

He looked at me, as though I had just asked a stupid question, which I suppose I had.

The sun had gone down on this warm bright day a couple of hours ago. I waited for his lecture on personal safety precautions, but instead after a pregnant pause, he just uttered ’Because sometimes thick fog can come down very quickly and you might get lost.’

‘What!?´I exclaimed with incredulity.

As the heavy chains that bound the wrought iron gates together were unleashed, I felt like I was being let out on parole. This really bugged me. It ran contrary to my tried and tested lifestyle, where ‘freedom to wander’, eat late’ and ‘drink late’ are near the top of my vocabulary phrase book.

Darkness and the Complex manager

And now here I was being similarly chastised by the manager of the Government Tourist Complex in Fatehpur

‘But why’ I asked again trying to extract an explanation for the Manager ‘Why is it dangerous after dark?’

‘Because, in the dark you can easily get lost. There are also plenty of dishonest men about, who realise that you probably have your passport and other valuable items on you, which to them can be worth lots of money. And of course, if you can afford to frequent this hotel ……… Well, I don’t need to say any more. Just please be careful sir.’

Well, that was frank enough. No evasive answers this time. No ‘Because the fairies might blow you over.’

‘My friend here will give you a lift back on his motor bike when you have finished your beer. If you want to stay longer, that is no problem. Whenever you want to leave, we will give you a lift.’

The notion of ‘bother-in-the-back-sticks’ was alien to me. Back home, being downtown, late at night and alone would seem to be more of a threat to personal safety, than wandering about through some rural landscape.

I had read a number of books about the Sub-Continent in the year running up to my visit, which weren’t exactly geared up to increasing the tourist trade. William Dalrymple’s erudite study, The Age of Kali (Age of Kali – Our Book Review), was by far the bleakest. Was the metaphoric storm cloud that he painted about to burst upon me during the short motorcycle ride home, unleashing all manner of caste and political violence, gun running and drug wars?

Paragraphs of darkness

The items that caught my eye in the newspapers I bought during previous trips to India concerned traffic accidents. Extremely serious collisions involving multiple deaths were reported as though they were just an everyday occurrence. Their reportage was usually relegated to a couple of paragraphs inside columns.

After leaving Fatehpur, I glanced through the stockpile of newspapers that I had bought over the last week. The headlines were frequently tedious, regarding, for example, the long-winded progression of a two-hundred-page Parliamentary report through a labyrinth of committees, sub-committees and working parties. It felt like technocracy masquerading as news– an obsession with process rather than content.

Similarly, the week before flying to India, I searched the Internet websites of Indian newspapers for juicy snippets that were currently making the front pages around the Sub-Continent. A mundane collection of leading articles gave the impression that there really wasn’t an awful lot going on in this great melting pot to interest your average citizen. Witness, if you can stand the tedium, the first three items listed by the Times of India’s website on 2.12.99:

‘Congress presses for amendments to IRDA Bill’: New Delhi. The congress finally decide on Wednesday to support the controversial Insurance Regulatory Development Authority Bill, provided the Government accept four amendments …… ;

‘Supreme Court issues notice to Punjab Government on Lok Pal issue’: New Delhi. The Supreme Court on Wednesday issues notice on a petition filed by Punjab government challenging a Punjab and Haryana High Court Judgement quashing appointment of Justice Harbans Rai …..;

‘Supreme Court quashes EC probe against Manohan’: New Delhi. The Supreme Court on Wednesday said the election Commission’s inquiry against former finance minister Manmohan Singh to determine whether he was an ordinary resident of Assam for the purposes of his election ….

Wasn’t there more newsworthy stuff? I now turned to the side columns of the newspapers I had collected during the last week in search of an answer.

Here, condensed to the odd paragraph in those side columns was a spate of snippets about deaths. These contained the usual highway collisions but were now being outstripped by stories about multiple murders. Here are a selection of the ones that caught my eye:

‘Naxals go on rampage, killing 5 in Andhra‘ (17.12.99 Indian Freepress, Indore);

‘Militancy continues unabated in Tripura’ (25.12.99);

‘Eighteen killed, 30 hurt in Srinagar blast’ (Times of India);

‘Two gangsters held for killing policeman’ (Times of India, 13.12);

‘Three women killed as militants burn huts’ (Times of India, 14.12)

Militants gun down 8 J & K police personnel’ (14.12 Times of India);

‘Gang wars, killings keep Delhi cops on tenterhooks’ (17.12 Indian Free Press);

‘3 killed in Jamnagar firing; probe ordered’ (14.12 Indian Express);

‘Sena leader shot dead. Two hitmen held’ (Indian Express 14.12);

‘Gangster shot dead in Mira Road encounter’ (Indian Express 14.12).

So maybe all those warnings I received had some substance to them. It just served to re-emphasise for me that no matter how well versed and forewarned I was, no matter how much a state of equilibrium seemed to exist in villages or cities, there were always likely to be tensions simmering away under the surface, hidden from view and not readily talked about.

The only consolation I was able to take from this dark picture was that it did not appear to involve indiscriminate murder. So, unless I strayed inadvertently into the crossfire ….

The raiding of the State Bank of Bihar and Jaipur

I had spent the last week surrounded by a range of Moghul architecture and was in danger of turning into mausoleum. A remedy was at hand to prevent me getting severely ‘tombed out’. The Keoladeo National Park, near Bharatpur, was only seventeen miles away, just across the state border in Rajasthan. This contained India’s most famous bird sanctuary. To quote from the Rough Guide ‘Few places in the world …. boast such a profusion of wildlife in so confined an area.’

The morning’s proceedings got off to a bad start. Fatehpur does not have any banking facilities and the Rupees I had in my pocket had just about run out. I had barely enough to get me to the banks of more sizeable Bharatpur.

I left the guesthouse at 11.30 am, which left me with two and a half hours to cover the short distance to Bharatpur before the banks closed. Finally at 1.50 pm the shared jeep I had caught from Fatehpur pulled into Bharatpur. I jumped into the nearest rickshaw and said, ‘Just get me to a bank quick.’

First it was the Bank of India. Alas no foreign exchange.

Then it was the State Bank of India. Still no money change.

Finally, after a frantic drive through back streets and bazaars, I got decanted onto the steps of the State Bank of Bihar and Jaipur. The clock read 2.05 pm, five minutes after closing.

I strode purposefully up to the front counter and held up a traveller’s cheque. ‘Will you change this?’ I asked worriedly.

“Yes, over there”, the desk clerk replied, pointing behind him to a booth marked ‘Exchange’.

Phew, I thought, they do, and what is more they are still open. Well time keeping in India was lax on many fronts. Why should banks be any different?

‘Hi there’ I greeted the clerk at Exchange confidently. “Please change this fifty-pound traveller’s cheque.’

‘No, I am sorry, we are completely closed.’

‘But your colleague at the front desk just told me you would change this for me’ I exclaimed. ‘Can’t you just change this one cheque?’

‘You don’t seem to understand Sir, our accounts have now been signed off and balanced for the day, our ledgers are shut.’

I was getting increasingly exasperated by the second. I was more or less Rupee-less, not enough to get me back to Fatehpur or even to pay for a bed for the night in Bharatpur, until the banks reopened.

“Look, I have no money at all. Is there no way in which you can help me? I’d be very grateful”

“Like I said sir, I am very sorry.”

I cursed my bad luck, using a phrase which I hoped wasn’t in any ‘Hindi – English’ dictionary he might possess. It was my fortieth birthday and the realisation that I might not have two Rupees to rub together in this remote Indian town, on my momentous evening was starting to grate deeply.

Finally, it occurred to me that I might have a trump card in my back pocket. I pulled this out and placed it on top of the clerk’s Holy Grail, his ledger. Would he treat this item of mine as a ‘get-out-of-jail’ card? He picked the passport up. I had already opened it at the personal details page, and he now held my vital statistics close to his eye.

‘Look you see this’ I said sternly. ‘You see this, my personal details. Look, my date of birth, forty today. I have no money. Please give me some birthday money. Forty, big birthday, yes?’

He continued to scrutinise the passport and then after a short pause said, ‘Just one moment Sir.’

There followed a remarkable turnabout in customer-care. He shouted over to some big wig and showed him my details. The big wig called for an even bigger wig, the manager, who came over. After a brief conference the manager turned to me and said “Sir, we do not normally do this, but because today is special for you, we will make an exception. We will open the bank again, just for you, but this is most unusual for us. You understand?’

‘Why sure’ I said, adding in a rare moment of extreme gratitude ‘May you be the father of a thousand sons.’

I filled out the necessary forms in triplicate and was then escorted to the front desk, whilst the necessary paperwork was sorted out behind the scenes. The manager sat me down behind the counter, between two clerks.

I looked straight ahead. The concertina iron gates that led out onto the street had now been drawn and padlocked. The ageing security guard who slouched on the steps ten minutes ago as I leapt out of the rickshaw, had clocked off and joined the three of us. As he stood behind me, I was hoping that the safety catch on his rifle was on just in case he suddenly tripped over his paunch. These negative thoughts were not helped when I caught sight of the corporate logo on his uniform, ‘Group Four’ – A bye-word back home for incompetence in the security business. Was India a kind of Siberia for the company’s errant employees?

Meanwhile, word about me had got around the Bank. One of the counter staff I was wedged between grinned and said, ‘Sir we are sending you our congratulations.’

His colleague then used a catch phrase which seems to demonstrate his nostalgia for the bye gone era of the Raj, ‘Sir (with a bow of his head) we are at your service.’

Ten minutes later, having expressed my indebtedness for this ‘beyond the call of duty’ transaction, and with a bundle of Rupees stashed around my body, I stepped out into the afternoon heat. This was not the kind of experience I could ever imagine having down my local Nat. West – its staff going beyond the call of duty to provide me with some beer money.

The only thing missing was the complementary tea and biscuits.

At the Sanctuary

The three-mile ride from the bank to the bird sanctuary was intriguing. Armed policemen lined both sides of the road, at a hundred-metre intervals, rifles at the ready. I wanted to enquire about the possibility of a hundred-gun salute for my birthday, but they looked a mean bunch with a definite purpose. So, what might that be?

I did not have to wait long for the answer. Fifteen minutes later having hired a bicycle and accompanied by Ashraf, my official guide, we were cycling along the main track through the sanctuary. Ashraf pulled me over to the side. Along the centre of the track approaching us at speed was a long cavalcade of white Ambassador cars and jeeps, with Rajasthani and Indian flags fluttering from their wing mirrors. The procession seemed to last for two or three minutes.

‘The Prime Minister of Rajasthan’, announced Ashraf, my guide.

‘He seems to have a lot of friends. Are they all ornithologists?’ I asked.

But there was no need to be a pansy-picking ornithologist to be able to appreciate this natural setting. The range of birds that passed through this place, en-route from all corners of the globe was highly impressive, from rare eagles to the White Breasted Kingfisher, from the Black Neck Stork to the Siberian Crane. All manner of species lurked in the surrounding swamps and lakes or squawked from the sides of the tracks. Not that this was solely an ornithologists’ paradise. Lesser spotted antelopes, wild boar, pythons, and turtles were also out there – not forgetting the occasional tiger, which in rare moments of high alert for the Park’s rangers put in an appearance.

Equally impressive was Ashraf’s infinite knowledge of the sounds, hiding places and migrating patterns of many of the four hundred different species. Cycling down some dirt track, my lobes were oblivious to anything other than the blanket sound of herons from nearby swamps and the grinding of our tyres against gravels

Ashraf would stop. “Can you hear that?”

“Hear what?”

He would then separate a couple of nearby bushes, rapidly assemble a pre-Patrick Moore telescope and tripod, tip the contraption at the right angle for me, and there amazingly the creature was, yet another variety of Kingfisher or something like that.

At one point, he pulled up sharp. ‘Look two birds copulating.’

Really? I thought. A birthday treat. I snatched his binoculars. ‘And pray, what are these called?’ I asked, bringing the lenses up to my eyes in a hurry.

‘These are parquets. Mating parquets.’

Oh well, some you win, some you lose, but well spotted that guide anyway.

We trundled down more dusty sidetracks. After another hour of him playing ‘name that bird’, the sun started to set and closing time was imminent. As we pulled back onto the main path Ashraf said, ‘Before I finish, I want to show you a bird record.’

Oh no I thought, now it’s time for the hard sell, as in, ‘I take you to my father’s shop, many good sound recordings of the park’s wildlife, very cheap price.’ He had been a very amiable chap throughout our expedition, so why did he have to start ruining it with all that mercenary stuff at journey’s end?

‘No thanks. No bird record’ I replied firmly.

He seemed stunned.

‘But many visitors look at these records. Just for one minute we visit this place,’ he said

I did not have the energy to argue and so relented.

We arrived at a crossroad and there it was. A marble monument six foot in height that took up nearly as much floor space as a prime minister’s cavalcade. Inscribed on this slab in intricate detail was an account of all the hunts and shooting sessions that had previously taken place in this former playground of Maharajas, until the practice was outlawed in the 1960s.

We had been at cross-purposes. For ‘bird record’ I had read ‘audio’ and ‘you buy, you buy’, whilst Ashraf had been talking ‘stone’ and ‘inscriptions’.

Across the top of each segment of this huge slab there were three headings: Date; ‘on the occasion of the visit of…..’; and ‘Bags / Guns’ (number of).

The Prince of Wales did not do too badly for himself during December 1922, with a mere 221 birds slaughtered. Mind you he wasn’t quite as good a crack shot as the Crown Prince of Germany, some eleven years previous. As for the Shah of Iran in 1931, well it was a case of could do better if only he tried.

All this in the name of leisure time pursuit – a self-styled population control of the skies. I wasn’t sure whether this giant slab was a celebration or a memorial. Perhaps it would have been more of a politically correct detour, if the final destination on our outing had, after all, been a record of sound bites rather than this essay of slaughter.

Lorries, lifts and liquor

It was now dusk. I waited by the busy roadside opposite the entrance to the sanctuary with a smattering of other expectant passengers for an apparently imminent bus. As time marched on I became less confident of ever getting back to the guest house that night.

It proved to be a cruel hour. In the pitch-black night, every two-minutes an approaching lorry had the tendency to look like a bus. My heart would leap and then sink as the reality was made plain.

Looks like it’s going to be a bummer of a fortieth after all, I thought.

Behind me was an open fronted shack, which housed a liquor store. Its sole occupant lay on a camp bed surrounded by booze and silhouetted by a bulb which struggled to emit twenty watts of light. I tried to envision the likely outcome of giving up waiting for the bus and asking the salesman if he had a spare camp bed for the night. The two of us could then drink ourselves to oblivion, just three strides away from the wheels of juggernauts, as they careered down the bleak Bharatpur–Agra highway.

Another more realistic but dangerous option had meantime revealed itself. The youths at the bus stop were trying to hitch lifts from passing lorries.

The technique seemed to go like this:

Step off the path into the roadside, praying that as you get dazzled by the lorry’s spotlights, its huge tyres are not too close to the gutter; wave your hands about frantically at the phantom driver. As the driver slows down to ten miles an hour, run like hell alongside the vehicle, flinging the passenger door open; with the truck still moving, fire some rapid questions concerning where the driver is going, can he help you, how many Rupees and so on; and if all is agreeable, haul yourself aboard, with a couple of your mates following up behind you – All without the driver stopping.

I spent an hour witnessing this spectacle. However, it must be said that only a minority of those who attempted these ‘running’ negotiations with passing drivers finally disappeared in the front of (as opposed to ‘under the front of’) a truck.

I made some mental notes about the essential techniques of hitching a lift Bharatpur style, particularly how to avoid getting your legs smashed to pieces, as you stepped out all too close for comfort next to the lorry’s wheels. But of course, this would have only been half the battle. If I had managed to successfully fling open that door, what were the chances of making myself understood, assuming that driver was not conversant in English, and of course there would be no accounting for dialects and the number of ways it was possible to pronounce Fatehpur Sikri.

Finally, I was saved from the dilemma of having to choose between death by crushed bones or alcoholic poisoning. A bona-fide bus pulled alongside, and with the rest of the madding crowd, I fought and elbowed my way onto the bus’s steps. I wasn’t going to be left behind on this occasion. As the driver pulled out, I looked behind, and with a perverse sense of satisfaction caught a glimpse of the many prospective passengers who did not make it onto those steps.

Down the bazaar

I decided to spend my last afternoon in Fatehpur sauntering around the village that lies just to one side of the mosque’s sheer steps. Running through the heart of the village is a narrow half-mile long bazaar. It was lined with open fronted shops which were either painted in a loud gaudy manner or had a soft pastel focus. Both the contents of these shops and the cacophony of life that passed through the street, I found to be mesmerising. In many respects it felt like things had not changed here since Akbar’s time.

On one side of the street women in emerald green, amber or scarlet saris squatted on the dusty floor surrounded by sacks of red and green chilies, turmeric, garlic, cinnamon and a host of other spices; Opposite them more women squatted amidst sacks of fruit, vegetables and the tools of their trade, scales and accompanying weights.

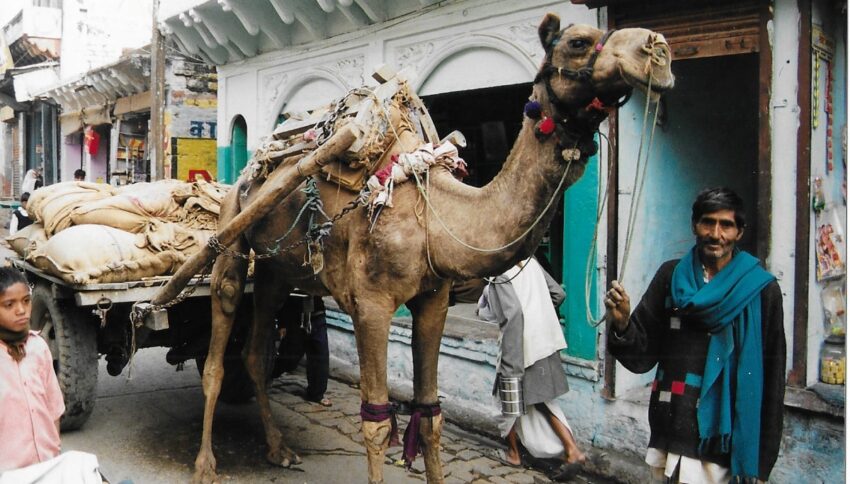

Young boys pushed wooden carts, with nuts roasted on top of smoking braziers; donkeys were hauled down the street laden with bricks; camels pulled carts containing a range of merchandise for delivery to shops along this track. Hogs scuttled their way through the bazaar free to do whatever they wanted.

The open fronted shops reflected a variety of crafts and industry: In some of these establishments men folk just sat quietly reading newspapers, keeping a casual eye over their bangles, carpets, leather goods, religious icons, wool, or pottery.

In other cases: the nature of the trade meant the vendors could not just sit back by their stockpile in contemplative mode:

the goldsmith was busy making jewellery, with his pliers, scales and eyepiece;

the laundry and ironing wallah was slaving over his ironing board;

the curd wallah was constantly stirring his huge black vat on top of a kerb side fire, leaning from side to side to avoid the billowing cloud;

the pokhara wallah sat next to him, with another vat, deep frying a range of Indian vegetables;

the Indian medicine wallah was emptying a specialist brand of dried leaves out of a jar into his scales;

the Western Medicine wallah was holding a consultation;

the tanner wallah was pouring used red dye into the gutter;

the sewing wallah was peddling furiously stitching braid to saris;

the bicycle wallah was repairing punctures and hammering old bent out wheels back into shape;

the village barber shouted out from his throne ‘Hey Mister, your hair is too tall it needs cutting. Only ten Rupees for your hair cut.’

The list was endless. There were enough separate trades to line this stretch.

There was nothing unique about this compact, yet trade wise, diverse bazaar. They are strewn across the Indian Sub-Continent, but this had a very different feel, with Akbar’s fantastic legacies towering up behind the bazaar’s back streets.

The curiosity shown to me by the stall holders and the constant procession of humanity from the age of five to adult that came out of the woodwork and tugged at my shirt, made me think that the number of visitors to Fatehpur Sikri who made the side step from the monuments to the bazaar were few and far between – a case of busing them back to Agra quick, before their half-day excursion could threaten to spill over into the afternoon.

Equally intriguing was how the local residents, or at least those who eked out an existence down the bazaar were almost oblivious to the spectacular architectural backdrop behind their stores.

The questions I was asked were not about which monuments I had visited and how they compared with neighbouring Agra. They were much more central to everyday life – ‘Where was I from?’, ‘Which town?’, ‘What profession?’, ‘My family?’, ‘How much did my clothes cost?’, ‘Would I like a tailor-made shirt within the hour?’, ‘How about some leather sandals or maybe some deep-fried giant chilies?’ ‘Ancient buildings? What ancient buildings?’

Akbar was dead, long live the bazaar.

Yardav and Family

I had reached the end of the bazaar and started to retrace my steps back to the clock tower at the top of the street. Here I met Yardav Sharma in front of his son’s pharmacy. He got up off his seat which straddled an open drain and edged his way into my path, introducing himself.

This wasn’t a kind of a ‘Hello Mister, where you from? You buy medicine from my son’s shop; I give you very good price.’ It was subtler than that. He spoke very gently and was in his mid-seventies.

‘Sir I have been watching you study all the shops down this street. Not many tourists come down the bazaar.’

He told me that he was a lifetime resident of the village and was a Brahman, although his rag-taggle appearance did not somehow meet up to the standards of this priestly caste.

Perhaps being a Brahman, I could have expected to hear some traditional views about long held cherished values and preserving the status quo.

He told me how his father had built the family home in Fatehpur, just before he was born and was a political prisoner under the British as part of Gandhi’s movement of passive resistance.

‘My oldest son was born during the year of Independence’ he said nostalgically.

‘Ah 1947’ I stated authoritatively.

‘No, 1948’ he corrected me.

‘Have you heard of freedom at midnight?’ he asked

Was this about some secret mass exodus from the village that evening I wondered?

‘Freedom at Midnight’ he repeated. ‘Do you know of this. It’s a famous book about India getting independence from the British. You should try to find it before you leave India.’

‘But who are its authors?’

‘Domeniquee Lapierre and Larry Collins’ shouted Bram’s son from behind us. He had overheard our conversation and retrieved a well-thumbed copy of the publication from the draw under his pharmacy counter.

Take two Diacalm and read one chapter of the book every four hours, I was waiting for him to say, It’ll work wonders for your diarrhoea.

We mounted the steps into his shop, where he had poured cups of coffee for the three of us.

I decided to play devil’s advocate. ‘So Yardav,’ I asked ‘the country has obviously gone from strength to strength since Independence. You did not really need all that British Rule stuff after all?’

Given his father’s background, he was surprisingly noncommittal.

‘There have been good and bad things that have happened since Independence, just like in most countries.’ ……….

……. ‘But the worse thing about Indian society since 1948 has been the massive population growth. In one year, we are predicted to hit the one billion mark. When I was born in Fatehpur Sikri, we only had a population of 3,000. Now we have reached 30 000. But of course, this is nothing compared to the big cities. – the country is collapsing under the strain. ‘……..

……. ‘I think in your schools they teach youngsters about matters like population control and AIDS, but there is little awareness raising of issues like that here. ‘

He talked about the arrival of electricity in the village after Independence and then of the appearance of the first television in this settlement.

‘Before the first TV arrived in Fatehpur, no one knew about the existence of all those erotic temple sculptures at Khajuraho. They have been there for thousands of years, but because they are in such a remote place, very few people were aware of their presence until we saw a TV programme about them. Then of course this was a big topic of conversation in the village.’

‘But presumably they did not screen it before 9 pm?’ I asked, being well aware of the explicit nature of these sculptures.’

‘Now my family has its own TV.’ he said proudly. ‘Why, last year we watched the football World Cup from France and then just a few months ago many people came to our house to watch the World Cup cricket from England.’

Being a rather forward-looking Brahman, he then leapt several generations from Marconi to Microsoft. ‘And now I hear about the internet. But I do my communicating by word of mouth, every day from the steps of my son’s pharmacy until 4 pm and then I go back home to sit up on my bed until midnight.’

Throughout these pearls of wisdom, Bram had been clutching a granddaughter to his chest. This impish child had been chatting away non-stop to herself. ‘She is a very mischievous girl’, Yardav said at one point. The girl then came out with a one-minute diatribe aimed at us both.

‘And now what is she babbling on about?’ I asked

‘Oh, she says that she is very worried about the exams she will soon be having at school.’

‘Exams? But how old is she?’

‘Nearly five.’

‘She says she has been having bad dreams about them, but I tell her, as long as she pays attention in class, she’ll be ok.’

He was then back onto technology.

‘You have a camera, yes?’

I showed him my sluggish single reflex lens apparatus, which he seemed to think was a bit outdated and he was right.

During the course of our talk, groups of passers by, both adults and children, would stop at the bottom of the steps, straining their ears to hear our conversation. Not that they were able to stay there long. Yardav would turn around and say in a stern manner, ‘Yes can I help you?’, and they would be on their way.

‘If you want,’ he said ‘when you have finished exploring, you can come back to my house, meet the rest of my family and drink some tea. Here is my address, if my son is not at his pharmacy when you come back, just show it to any of the nearby shop keepers, and they will guide you through the medina.’

Three hours later, I entered through Yardav’s front door. He was perched on his bed, with an assortment of sons, daughters, in laws, and grandchildren clustered around its base. He held the youngest grandson in his arms, a baby of a few months with wide staring dark eyes. Not wishing to be out done, the impish granddaughter, who he had held down the bazaar, emitted another diatribe. ‘Now what is it this time?’ I asked

‘Oh, she is saying that you look like one of her schoolteachers’, interjected the girl’s father.

I sipped tea, ate ginger biscuits, and watched Yardav getting back onto his quest for general knowledge.

‘I have also been reading about the existence of the Euro currency. Tell me how many Deutsch Marks there are to the Euro are and what are the reasons Mister Blair is holding back on joining this system?’

Come off it Bram, I thought, there’s more chance of that baby you hold passing his physics exam, than me giving you chapter and verse on the Euro. I compromised by promising to send him some Euro coins when they come into circulation – He knew the launch date, I didn’t.

One hour later Bram said, Damian if you have a train to catch tonight, I think you better be getting back to your hotel. As a parting shot, he asked me, once back in the UK, to search for a western book for him that had been reviewed in the Times of India.

He jotted down the publication’s details, which were thoroughly in keeping with his liberal views on taboo matters: ‘To have and to hold, Sex and marriage’, by Jenny Cozens. I bet he was a bit of a stallion in his time.

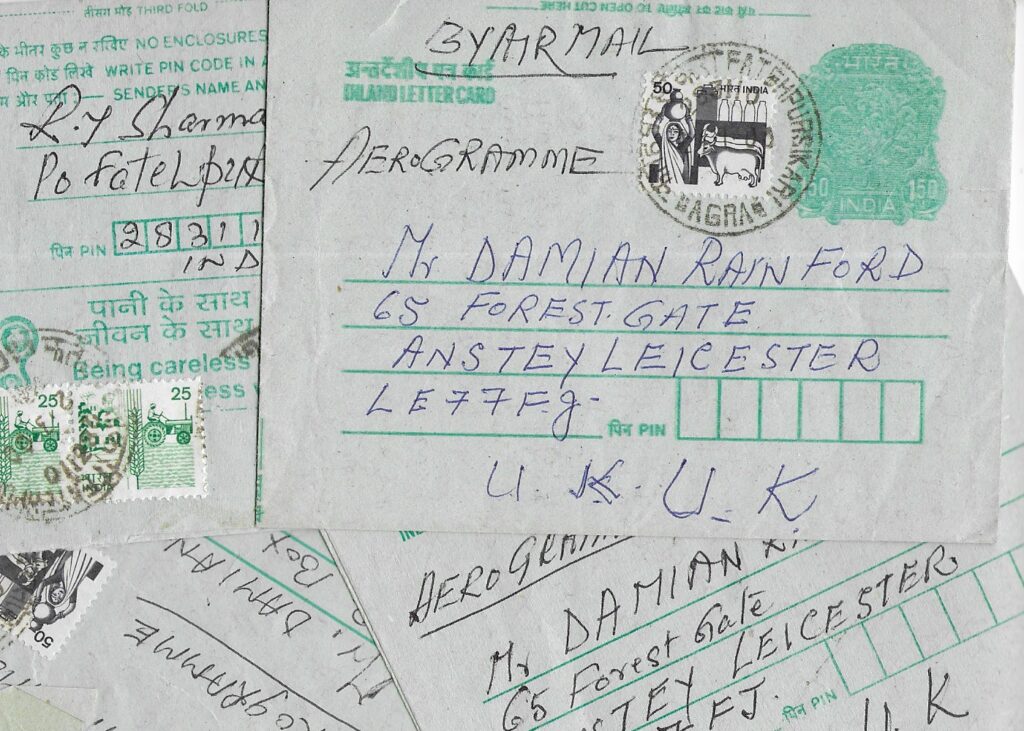

His last words as we parted company were ‘Please be very careful on the rest of your trip, use your eyes at all times to see what is happening around you and do write to tell me that you have finally reached home safely.’

Now where had I heard that before?

Damian Rainford (1999/2000)

Back Home to theancienthighway.com